Category Archives: Electrical

Who Knows What Week it Is?

Sorry we have been so long in updating our blog regarding our progress. As is usually the case, when things get really juicy, it’s when one is super busy. And such was the case with us. (We move in on Thursday!) We have been lucky to have friends come help, and the local sandwich shop guy asks every day at lunch how progress goes (he loves Lloyd Kahn, too!) And yes, we will be camping out. We have electricity*, a roof overhead, and a place to sleep, but that is where it ends, for now. But it can’t be that bad, as we are choosing to move in instead of paying for another two weeks of our current rent, which is an option. Or we’re pleasantly nuts, which is also possible. This is the theory some of our family has taken up.

The progress is as follows:

Reflectix installed between the rafters. That stuff is amazing. We ordered it figuring it would be a good idea given our current roofing is black underlayment, soon to be followed by aluminum sheeting, neither of which is known for good thermal cooling properties. Now we wish we had used it for the entire envelope prior to sheep’s wool insulation. Reflectix is similar to what lines your lunch bag – it has excellent radiant heat/cold insulation properties, advertised as 97% efficient. We can tell you, just by stapling that stuff up, without even the insulation to go over it yet, the indoor temperature was close to 10 degrees (F) cooler at lunchtime compared to our confused/sweaty/grumpy prior afternoons.

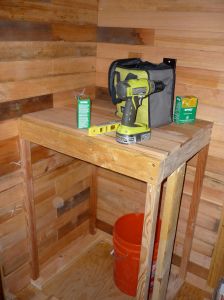

Next improvement was more paneling, and the installation of the shelf for the fridge and start of the closet underneath.

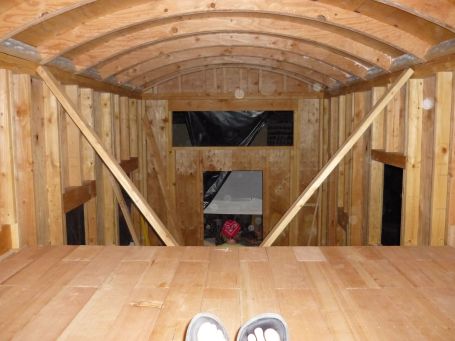

And more paneling in the loft area so we have a place to put our clothes and bed in a few days.

Also, electricity works in all circuits*. As mentioned previously, we have 4 circuits, (2) 15 amp and (2) 20 amp circuits. One of the 15 amp circuits, much to our chagrin, kept tripping the breaker when we fired ‘er up. Turned out to be a cable clamp that had been over-tightened, short-circuiting the wire. Also had a faulty GFCI circuit, new from the Big Box Store. As we closed up tonight, we realized that the kitchen circuit did not shut off when the breaker was switched, which was not cool. *We have since found that the breaker was fine; mislabeling and tired brains were at fault.The gas lines, similarly, have been a bit of a pain, which, when time allows, we will provide our reflections on.

Last but not least, the beautiful Dutch door is nearly installed. We love the rounded top, to match our rounded roof. And the hardware is all ready to go, same for the French doors.

And although the bathroom is not usable yet (take that back – the bucket has been, ahem, christened), we did put up a little curtain for privacy from the street while still having a little air flow while working. It stood as a foretaste of what our little house will be, so very soon. It will be a future full of house plants. It’s a cheery, domestic view.

Next time we post, we’ll be living & camping in our beautiful house! What better way to learn what you really need in life?

Weekend 11 of Construction

This weekend will seem rather boring on virtual paper, as it was mostly logistic, and we have a pathetic number of pictures as the usual photographer was busy doing the work mostly alone. But fear not, that won’t stop us from boring you with the details! You want the authentic experience, right?

Drilling nice, perpendicular, centered holes in studs that are closer together than 16″ o.c. is difficult, so the installation of the plumbing was stymied by a seemingly minor detail. A right-angled drill would make the job magnitudes easier, but we couldn’t seem to locate one, oddly. Even the Craigslisters who advertised ones for sale didn’t call back. We are hoping the NEPTL will help. Tool libraries are the cat’s pyjamas, so you should see if there’s one in your area.

We did install most of the 12v wiring since those holes are smaller and if they are less straight, no one cares. And we picked up our interior paneling, some very attractive 5/16″ thick by 4″ wide tongue and groove fir. Again, it was salvage and in mostly short sections, but looked like clear, close vertical grain, suggesting old growth (without the guilt). Also, a friend of the family has offered to give us all of her pine trim from her house build that she didn’t use, for free. So supplies are coming together. Happy day!

One of us, who shall remain unnamed, was having a bit of a heart attack over the weight limit of 10,000 lbs, as we are currently sitting at a little under 7,000 less tools and extras. So, after some serious panicking, we learned the difference between linear feet (lf) and board feet (bf) when calculating lumber weights. They are not the same thing. Linear feet is what you’d first think of – the actual length of lumber, but it is difficult to calculate weight as widths and thicknesses vary. Board feet is an assumed 12″ wide by 1″ thick piece of the wood you are choosing, even if the boards you are buying are not 12″ wide by 1″ thick. So board feet is the more helpful but confusing number, as it is a volume of wood rather than a length when calculating the weight of piles of lumber. But bf was exactly what we needed when deciding on our future lumber choices for siding and paneling. Board feet is used most commonly for hardwoods (as opposed to the softwoods most often used for framing), and is calculated either as width (in inches) x length (in feet) x thickness (in inches) x 12, or as width x length x thickness (in inches) / 144. Then you can figure out the weight, for a given moisture content (wetness) of the wood, based on standard values for 1000 bf, which you can find in tables all over the internet. We realized we will be heavy, but not catastrophically so as originally miscalculated! Hence finding 5/16″ paneling, instead of using the ubiquitous 3/4″ thick pine tongue and groove. Fir is slightly heavier than pine, but when you are looking at something less than half as thick, it will be much lighter. And we did install a small wall’s worth of paneling, just to get the hang of it and feel like the weekend wasn’t a wash:

The wood will need to be sanded, but we kind of liked the “rainbow” effect. And we fluffed and filled with wool insulation as we went. Very gratifying.

Also, the weather portends rain in a few days, so we were very excited to have our Grace Ultra underlayment arrive. It was the least toxic waterproofing roof underlayment we could find, to go underneath our aluminum sheeting, so it had to be high temperature rated. Instead of being made from asphalt rubber or plain tar paper (all nasty fossil fuel based things that reek) like most, it is made from butyl rubber over a sheet of essentially Tyvek. Still fakey, but hopefully not as bad. We also ordered Reflectix, which is glorified bubble wrap with a metallic foil coating on it, to block radiant heat from the roof, as that seems to be the main source of the heat coming into the house. It has an efficiency rating of around 97%, which seems like a darn good number. So that will be installed just inside the roof sheathing, followed by wool and then paneling. Should be nice and cozy.

Last thing is the thorn in our side: the propane system. In addition to the abovementioned hole drilling problem, there are other obstacles. This one, it seems, the “Experts” have cornered the market on. As we see it, there are three main choices for running gas lines in a tiny house: black pipe, which is heavy, stiff, and a real pain to install, flexible copper pipe which requires careful installation and specific fittings to be airtight and has a much smaller diameter (at least all that we could find), and CSST (corrugated stainless steel tubing), which I have mentioned before. All brands of CSST have proprietary, non-interchangeable fittings. You can buy the first two types of gas lines at Big Box stores (the copper pipe can be found in the “icemaker” section, near the fridge stuff), and you can buy one type of CSST online from a certain Big Box store, namely AlphaFlex, which is the same thing as Homeflex. However, AlphaFlex/HomeFlex are made with PVC. There are other brands, such as ProFlex and TruFlex (I don’t know if they are affiliated with each other) which use less toxic plastic coatings, and their fittings also include a rubber gasket, which seems like a really good idea. However, all of the above types of CSST and fittings cannot be found in a brick and mortar retail store in this town. In fact, if you call any place that advertises that they stock gas line stuff, they get really huffy when you inform them that you are “doing it yourself” and tell you how you couldn’t possibly know what you need and should have an Expert determine that for you. Puckey, I say. So we ordered on Amazon. Even ordered the how-to booklet for installers who want to get “certified,” and it doesn’t look like a very long read! We’ll let you know how it works out. So far, the lesson learned is: do not be optimistic in your lengths of line. Patchwork propane lines are frowned upon, obviously. The good news on the propane front is that we have a sympathetic uncle who knows how to pressurize the system as required to check for leaks, and has all the fittings to do so! So don’t worry, we won’t be endangering anyone with our propane system, sans Experts.

This week, we hope to install the Grace Ultra in time for rain, and continue paneling and insulating as we finish installing the necessary pipes. May even wire up the switches and receptacles, so the house can be “plugged in” and have actual lights on!

Weekend 10 of Construction and The Big Move

This was one heckuva weekend, with mad buttoning-up of things for travel on Sunday. The doors had been neglected until now as they require extra attention (such as custom door jambs) to install; the French doors were originally fixed glazed doors, and about 18″ too tall for the under-loft area, so they had to be carefully cut down, glued, and clamped, and a jamb made. The bottom sill of the French door jamb was made from scrap white oak, with a carefully-cut slope to it so that all water would drain (you can’t buy 4′ wide sections of metal threshold/sill material at the Big Box Store). It’s one of those niceties we will appreciate although it might not be obvious to the casual observer.

The 12v DC wiring did not have a functioning breaker panel to connect to, so the Ebay boat panels were torn apart, sanded clean (’cause they’re old and made of metal, not cheap plastic), and re-assembled with the proper breaker sizes (primarily 5-10 amp). We made a little housing for it so that the rear of the panel can be accessed for maintenance. The breaker switches are also the on/off switches in this case, which works fine. We think it looks steampunk, which is always good!

And in the process, gained great respect for Ace Hardware over other Big Box Stores – we always liked that store over the Big Box, and learned that particular bias from our respective dads. Coincidentally, it seems the place is staffed with DIY dads. Well, another reason why I love them: I called the plumbing and electrical specialty store in town, and after passing me around, found one guy who “kinda” knew 12v – by which he meant, he could discuss LED lighting with you, and recommended I visit the auto electric shop in town to get advice for real 12 volt stuff. I view that as good customer service, nonetheless. But I went to Ace first, just in case, found a great selection of wire for my needs (10-16 AWG, or American Wire Gauge, wire), and the first guy that walked by I posed the same question to: “Do you know anything about 12 volt?” and he answered, “I know all about 12 volt,” as he pulled wire. This surprised me. I asked why, and he said he had previously wired RVs for a living! At this point I freaked out and asked him all the questions I could, since he was the first person I met who knew anything! Here are the highlights:

1. What is the recommended treatment for wire junctions/terminations (i.e. electrical boxes)? Answer: none. You can end the wires in the middle of the wall, just put a couple wire nuts on the bare ends, no box needed.

2. Does it matter if you use larger gauge wire than required for the load or distance? Answer: nope, only a problem with smaller gauge wire than required. It’s just a little more expensive.

3. Where is the best place to get 12v wiring? Answer: auto supply stores often sell rolls of 14, 16, and 18 gauge wire by the 25-50′ for cheaper than by-the-foot wiring. The larger or smaller stuff, get here.

4. Does the color matter for positive and negative? Nope, whatever colors you want. Many people use red and black, but any color will do. Just stick with the same colors so you don’t get confused.

5. Why doesn’t everyone use 12v systems when they are so cool and easy to use?? Answer: The power source has to be close due to losses over distance. Otherwise, no good reason. If you get shocked, “It’s not even bee-sting material.” Fire hazard is low. My note: You do, however, need to use 12v – approved switches rather than regular 120v switches due to the larger amperages, as they can actually melt the terminals of a regular switch if they arc. RV and marine stores sell 12v rocker switches, and the plain ol’ metal toggle switches seem to be used with no problems, either.

So I was stoked. If we ever do anything with the Palomino chassis, I’m doing all 12v DC, just for the fun of it. And maybe I can get my sister involved, too, as it seems 12v DC systems are a great introduction to electrical systems. Would have made my high school physics class WAY more interesting…

And we also installed the 120v, 30 amp RV electrical inlet and water inlet, in the newly lined utility closets (for vapor and spark protection). Since we are poor and don’t have our power center or inverter/charger for self-made power yet, but want to be able to plug-and-play later with solar, wind turbines, or generator, we put two gratuitous junction boxes in the utility closet and ran extra conduit through them, so that it will be easy to add those components later without having to try to run more conduit and have a messy cabinet. Messy electrical closets are ugly and bother me.

Word to the wise: you’d think there’s only one kind of 30 amp RV AC inlet. Wrong. There are two kinds – both have three prongs, but one is a regular plug and the other is a twist-lock variety. Both work, but they are not interchangeable, although they make adapters. The twist-lock variety seems a little more secure, so many of the new 30 amp RV cords have a female locking end and a male non-locking end, like this. Make sure you know what you are getting. I didn’t, and was surprised when I opened the inlet after getting it in the mail. Also, when I talked to Monty Taylor regarding “separable” vs “non-separable” power supply for RV inspection, he said he doesn’t care so long as it’s done well. However, I didn’t think about male vs female receptacles/terminals when I bought one the first go-round. I got a 30a regular 3 prong receptacle (female) for the house. Well, that doesn’t work. You need the plug (male) end installed in the house, so that when you hook up a cable, the male end is free to plug into your power source receptacle and the female end plugs into your house. Can’t have a cord with two male ends, can we? Duh. Good news: if you’re like me and you’re cheap, and you saved the cord from the pop-up camper you ripped apart (those power cords are $50 and up man!) that was permanently attached so one end is a stub with raw wires sticking out, you can buy male and female adapter heads online and at any RV store for less than $20. So that is what I did. I bought an adapter for my twist-lock 30 amp inlet to that we can use either type of plug, and bought a $17 female adapter head with standard RV 30 amp layout to attach to my raw cord. Clear as mud? Yeah, me too. Result is, we are ready for any type of 30 amp power supply! Mwaha!

Next, the utility closet got its cover and doors, and all the window and door openings were covered with plywood for the drive. Hurricane clips were attached from rafters to top plates to secure the roof, and we also added some straps to the front eave, for upward forces while driving.

For the moving day, procure yourself a heavy-duty truck to do the pulling, and a good, optimistic friend or family member to drive behind you and call periodically to tell you nothing has fallen off. And as Dee Williams says in her e-book, to also tell you, “It’s so cu-ute!” and soothe your nerves. In our case, have the calm ones in the big truck, and the documenters following behind (only if not driving, of course) and providing caravan-afforded protection from tailgaters and other silly people.

For those who look at our house and say “It’s so tall! Are you sure the wind won’t blow it over?” the answer is that it did great on the road. We had no concerns driving it whatsoever, and in fact it surprised all of us, in a very welcome way. The only thing that wobbled was the license plate, because it’s attached by a flimsy plastic bracket on the top only, which we can handle. Nothing flew off, nothing was broken. Sigh.

We do recommend using a truck weigh station to find out how much your trailer weighs, while you’re on the road anyway. You don’t have to pay, it isn’t hard, and the scales are always on, even if the station is closed. We found out, after much panicked calculations, that our house weighs about 800 more than we had projected, at 7,300 lbs. For those contemplating a rounded roof such as ours, do keep in mind that you will have considerably more wall height, and therefore weight, compared to a typical Tumbleweed gabled house. We did not consider that in our calculations. Oops. We are now left with less weight to work with in finishing, but with care we will still come in under our weight limit. If you look up Colin’s Coastal Cabin on The Tiny House Blog, he has a shed roof but similar high walls, and he came in at 9,000 lbs. His house is gorgeous and well-made. So be aware of weight! It adds up in a sneaky sort of way.

Now, getting our tiny house onto our narrow lot from our narrow lane with a large truck and rented power mover, that was a long story, to be discussed at a later date. The happy ending is: our house is now resting comfortably on our lot, with jacks to stabilize, and many neighbors already stopping by to ask questions, only 10 minutes away now instead of hours. About three weeks left until we move in!

Week 8 of Construction

This was a marathon weekend. Closer to a week of work, actually. We started on the 4th by cutting the 2×12’s for our couch back/bookcase/bathroom wall and installing the pocket door. Which was really cool, ’cause then we could really have a feel for the bathroom size (tiny – haha). By the way, if you decide to put your bathroom door at the end instead of the middle of the bathroom, I cannot tell you how much of a difference it made to make our bathroom 3’4″ wide instead of 3′. Seriously. Happily no one got a picture of me making the discovery by “trying out” the bathroom with a 5 gallon bucket and our wooden toilet seat, but it was suuuper tiny. Add four inches, and all of a sudden it’s pleasantly cozy. But I suppose that “inches matter” should really be the tiny-house-planning and building mantra. If you bought Tumbleweed plans, then you can grin your smug little smile and pooh to my mantra. But for those like us: your happy little pencil sketches get stretched and squeezed like you wouldn’t believe with the addition of a single 2×4, and all of a sudden it is a crisis figuring out how to allow for the window trim. That’s character and wisdom gained, right there.

But I digress. We noticed that everyone puts the toilet on one side of the door and the shower/tub on the other, using a doorway in the middle as the bathroom floor space, and then they put the kitchen under the loft next to it, so that both are claustrophobia-inducing, but very space-efficient and share the same sink. But we didn’t like the idea that efficiency is the highest good, and bathroom sinks can be really small, if you even want one. We both love Alexander’s A Pattern Language, and decided that the archaic “we have servants do all our cooking, so let’s put out kitchen in the closet” idea is stupid. So we put our space where we spend our time (in the kitchen, as for most people), and made the under-loft our “intimate” space, such as seating. We also designed our house so that the farther into it from the front door you get, the more private the space, which is also comforting and intuitive. Those two things were made possible by running the bathroom along the back, which, unlike the kitchen, makes sense to put in a closet. Plan is to make the front face of the pocket door a slightly shallower continuation of the bookcase (paperback novels, anyone?!), which also serves as the bathroom wall. We’ll put tongue and groove and/or Magnum board on the bathroom face of the bookcase, and the couch will sit in front of that, with bulk storage cabinets in the seat and the couch back, and faces out. We have some nice French doors under the loft which, later on, will be continuous with the patio and the couch area.

Next up was shaping and cutting the loft joists out of 2×6 cedar-with-character as the father-in-law puts it, which required careful planning of what to cut and which joist went where, with what face. But we all agree that the careful planning of the joists really adds flair and craftsmanship to the design. I think it makes the house look Cascadian, or Scandijapanavian, our favorite styles 🙂

We also had the brainwave that we could skip placing a joist over the middle of the shower stall, and just use a block across, since it only has to span 3′. That gave us a lot more headroom in the shower, which is great. Might be a good spot to showcase our large piece of copper sheet. Downside it that the small, efficient, low-noise exhaust fan/light that I was going to install between the joists now has no good place to go, because all of them are designed to fit in a 6″ deep wall, unless they are the cheesy RV variety. It will probably have its own box made in the upper corner near the water heater, and the exhaust will just have to take a slightly more circuitous route to escape. No spilt milk.

Then we laid the loft boards, which I am in love with. They are short cuts of close, vertical-grain fir 1×6; leftovers from someone else’s project, and perfect for our purposes. We used the nail gun for a nice clean look. And as soon as it was done, day 2 was over with. Some teenagers immediately claimed the loft, located a mattress, and camped out for the night.

A party with passels of cousins, munchkins, and rainbows galore followed, so Saturday was a wash. Then there was the staircase. Sigh. Complicated, as it turns out, by the fact that we wanted a staircase instead of a ladder, with a wood stove underneath. Because staircases are usually well-supported at the top by a vertical wall or a heavy-duty set of joists, neither of which we are willing to concede. So it will be suspended from the ceiling, we think. Structural finish work, as the carpenters call it, can be fiddly business. So the stairs are TBD…

The other big victory was the placement of all the 120v AC circuitry in the house, made possible by another awesome dad and several trips to the Big Box of Chemicals & Sundries. That is, all the AC stuff is “stubbed in”, which means that the boxes and the wires are run, but the receptacles (outlets) and switches are not placed yet. But comparatively, that part just takes some logic and a morning of work (or so I say haha). The location of the AC panel was something of a conundrum, mostly due to lack of knowledge – in the dim hope we can get the house certified as an RV, we weren’t sure if the AC panel had to be placed within a certain distance of the power entry to the house (for boats it is within 7 or 8′, we hear), and we also did not want an electrical panel, humming with electricity in a stupidly-designed EMF-generating electrical panel, sited under our sleeping heads. For the latter, I still don’t know, because even though we bought a centered-load panel, the breakers don’t all sit immediately adjacent to the neutral bus bar. Grr. I hate being superstitious about that kind of stuff. But alas. The former requirement, I am happy to report, we do not have to worry about, as I’ll mention below.

We found out that the guy in Oregon to talk to about RV certification of a tiny house (which can, and has been done) is named Monty Taylor, the RV inspector of the Building Codes Division, and he travels all around the state. He can inspect a tiny house, and if it meets all the codes of a “park trailer” he can certify it as a homemade RV. Why would we care, you ask, since we hate permits and bureaucratic governmental interference and infernal fees? Because a recognized RV can be insured. Otherwise insurance companies view us and our houses as a hazard to their profitability. We aren’t super set on getting the house permitted, but if what is required and what we want to do are reasonably similar, then why not?

Here’s the juicy bits Monty told me, which for some reason I haven’t seen listed anywhere before (and Monty is a nice guy, so if you want to hear it straight from the horse’s mouth, call him on his cell, the number of which he lists on his office voicemail.) This is what he said: there are no structural requirements for a tiny house. For the electrical, you need Article 552 (on Park Trailers) of the National Electric Code (NEC), which can be found in the reference sections of most public libraries, and it’s only a few pages long, so just photocopy it so you can read the legalese at your own leisure. It wasn’t bad, and most of the stuff is really intuitive, like don’t have an electrical outlet within reach of the tub. Duh. For the rest of your utilities, such as humanure, propane, and freshwater, you’ll need the ANSI A119.5 2009 handbook on Park Trailers, which can be had from http://www.rvia.org for $41, as it currently stands. I just ordered my copy, so I’ll let you know how awful it is. Incidentally, there’s another book to buy on that site that looks like almost the same thing, but it costs $250. Don’t buy that one. Anyway, here’s the rundown on the electrical, in layman’s terms, in case it helps. Just think: if you don’t have any batteries, cords or solar hooked up, what better way to learn electrical safely, and have one less Expert to pay for minor house repairs down the line, than to wire your own tiny house? If not now, when? You can always have an electrician check your work when you’re done. However, do not sue me if you survive electrocution, because you read at your own risk!

1. Learn basic electrical concepts and terms:

AC = alternating current; because it alternates it can travel long distances from a power plant to your house. This is what your house is wired with: 110-120V, AC current. 120V current KILLS you if you are electrocuted, so you need to know what you are doing.

DC = direct current; this is what batteries generate, solar generates, and what RVs and boats use, because you don’t have to do anything to the electricity from your batteries/solar/turbine to run your equipment. You can get an inverter to do the job, but they are expensive and they use energy themselves, not to mention they are not 100% efficient at changing DC to AC, so you always lose power. If you’re going hardcore solar, you’ll need a whole lot of DC and not much AC. DC systems are usually 12V, which will not (usually) kill you if you electrocute yourself, which is nice. Incidentally, those blocky things (we call them “wall warts”) that are always connected to your phone charger and laptop charger change 120V AC to 12V DC to charge the phone/laptop battery. I didn’t know that until I started reading on electrical systems. I guess I thought they were surge protectors or something. That’s why phone chargers for your car don’t have a “wall wart,” just a cigarette plug, because they’re charging off of your car battery. Cool, eh?

amperage = amps are a measure of electricity per second. Think of it as the flow rate of electricity, like the flow of water through a pipe.

voltage = volts are a measure of the potential difference of electricity. Don’t cringe! Think of it as the pressure of water in the pipe. 120V AC power wants out of there bad, so don’t let it get you!

power = measured in watts, power is equal to volts x amps. It’s how much work something can do, like horsepower. Now practice. A 60 watt light bulb, plugged into a 120V AC standard outlet, uses how many amps?

resistance = the real-world factor. Some things are harder to pass electricity through than others. A smaller gauge wire will have higher resistance to flow of electricity, for example.

Parallel circuits – built more like a tree, with two trees with “branches” feeding the hot and neutral (respectively) of all the things on the circuit.

Series circuits – like a road trip – hot wire stops at the thing it’s feeding before starting back up on the other terminal and moving on to the next thing, neutral goes from the farthest thing on the circuit back to the panel

3 way switches – these are the kind that work in tandem with another switch to turn things on or off from more than one location. They require 3 way wire to allow the switches to work with each other

Wire – the gauge used is determined by the amperage of the circuit. The smaller the number, the larger the wire, which is not intuitive! The second number denotes how many wires there are, excluding ground (which is not counted). So your standard 15 amp circuit takes 14-2 wire, with 14-3 wire between 3-way switches.

2. Figure out what kinds of things you want to run in your house. Really. It’s a pain, it’s thankless, and it’s really intimidating for those learning electrical, but you really need to do it. It will help you learn, if nothing else. Get a Kill-O-Watt meter (available at the Big Box stores), and start measuring the usage of everything you will use, such as your laptop/computer, cell phone, toaster/toaster oven, microwave, fridge, blow-dryer, electric range/oven, and lights. Do it for days or weeks, not just a few hours while being eco-friendly is foremost on your brain. Keep in mind that things with digital screens on them draw “phantom loads” since they are essentially always on, even when not in use. And anything that heats things, like water heaters, ovens, rice cookers, toasters, microwaves, blow-dryers and clothes dryers, use HUGE amounts of electricity. That’s why people often forgo them or use propane or other fuel sources in a tiny house.

3. You will need to know how much energy you’re really going to use to be comfortable, because if nothing else, you need to know the size of your power cord. An extension cord only carries so much juice before you create a fire hazard or trip the breaker on your host house’s panel. Your three main choices, from what I can tell are: extension cord (look at the rating on the cord), 30 amp RV (3 prong) and 50 amp RV (4 prong)

4. Okay, if you’re still reading, this is what you do next: figure out what actual AC fixtures you want – lights, fans, fan lights, etc. so you know they’ll all fit (inches matter!) and not be overkill. Figure out where you want them. Do you want an outlet in your closet to charge your DirtDevil? How about Christmas lights? Patio lights? (The NEC Article 552 requires at least 1 outdoor outlet). Where do you want to charge your smartphone (hopefully not right near your head, the RF waves are not good) and your laptop? Alarm clock? A nightlight? A box fan for the two weeks in August in the Willamette Valley when you are sweating like a pig wishing for air conditioning? Done? Good!

5. Mark out where you want said lights, switches, outlets (receptacles) and fans. Write on the wall. Where do you want your power to come in? The Park Trailer code says standard is left rear, but I don’t know how they define that for a tiny house. Where do you want your panel so it is easy to distribute all the power coming in to your circuits, and easy to get to? Place your light boxes, switch and receptacle boxes accordingly, securing them in place with sturdy screws.

6. Divvy up your circuits. The Park Trailer article has a category of “2-5 circuits” which I think looked easiest to aim for. Many tiny houses have only 3 circuits. Most full-sized houses have 2 20 amp circuits for the kitchen, with dedicated circuits for ovens, microwaves, fridges, garbage disposals, etc.

What we did in ours:

– 4 circuits (overkill), 2, 15 amp and 2, 20 amp circuits, the bathroom/bedroom and main room lights were on a 15 amp, the living room, stairs and teeny fridge on a 15 amp, an outdoor receptacle and indoor one designed for an oil-heater (huge hog) on a 20 amp, and the kitchen on a 20 amp

– All single-pole switches except for two lights – the nightlight upstairs, and the fan light

– Metal-sheathed conduit from the main power feed to the panel

– A “kill switch” in the bedroom that cuts power to the whole bedroom and bathroom for sleeping at night. We will use an illuminated switch so we know when it is on. We have an outlet on top of our fridge for charging cell phones, far from our bed. Our concession to EMF and RF concerns.

– We designed our bookcase to have a compartment for storing our laptops and charging them, out of sight

– We will be installing only a few 12V circuits in the house – one for the fridge in case we ever get a fancy solar fridge, one for an outlet in the bookcase, the exhaust fan/hood in the kitchen (from an RV) and the water pump (from an RV). The DC panel has breakers instead of fuses (the fused type are the cheapest to get), and will go in the battery cabinet on the tongue. We haven’t wired it yet, but we will!